| Home News and Events |

|

eNeuroHow real is failed back surgery syndrome?

J. Rafe Sales, M.D.

Orthopedic spine surgeon, Providence Spine Services Patients who have persistent or recurrent pain after lumbar spine surgery are often grouped under the nonspecific rubric of failed back surgery syndrome, or FBSS. Some authors quote an incidence of FBSS of up to 40 percent after spine surgery. This term has become so ingrained in the spine vernacular that one might believe it implies a specific diagnosis for the cause of pain. This is not the case. In fact, presuming that FBSS is an end-stage or definitive diagnosis might preclude a thorough evaluation for the precise cause of pain. Compounding the matter is a prevailing therapeutic nihilism about FBSS. There remains a perception among some physicians that with occasional exceptions, once surgery or multiple surgeries have failed, it is rare to find a specific cause for the pain and in most instances treatment should be nonspecific and palliative. In fact, in most cases a structural, neurological or psychological cause for the pain can be identified. Multiple studies have demonstrated that up to 90 percent of patients have an etiology, determined by testing methods that are well established.

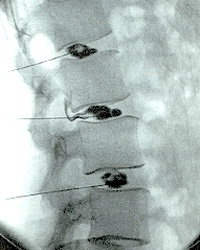

Figure 1: After a prior decompression, the patient sustained a fracture of the left pedicle resulting in severe pain and eventual instability. If a patient has persistent debilitating pain after spine surgery, one must begin with a detailed history and examination. The location of the pain provides the first hint of where to look. In the case of persistent back pain, the most likely causes are instability, discogenic pain or the facet joints. A patient with instability often will have spondylolithesis or hypermobile segment at the surgical level or adjacent to it. A patient with prior laminectomies or decompressions can go on to have significant instability if too much bone is removed during the decompression (Figure 1). Patients often complain of “start-up” pain, meaning pain when getting out of a chair or when initiating movement. If the patient has undergone a prior fusion but still has pain, then the instability could be due to a nonunion or a failure to fuse, which can occur in up to 15 percent of cases. Finally, instability can occur at a level next to a fusion due to increased stress across the motion segment. The key to diagnosing any of these problems is to use upright flexion and extension radiographs, as these often demonstrate the instability. A common cause of lower back pain

Figure 2: A discogram shows leaking dye from the middle segment, indicating a possible annular injury. Another frequently missed cause of FBSS is discogenic pain. Discogenic lower back pain is worse with sitting. Often, MRI or CT scans will reveal degenerative discs, a loss of disc height, and bony changes and edema. A discogram is used to evaluate the integrity of the disc as well as to evaluate for concordant pain with provocative pressure (Figure 2). When used properly, a discogram often can confirm the diagnosis of discogenic back pain. Other causes of lower back pain in FBSS include facet joint pain and sacroiliac joint pain. Facet pain can be detected on physical exam, is often worse with spinal extension, and is relieved with diagnostic facet injections and medial branch blocks. Sacroiliac joint pain presents as gluteal pain, and also is relieved by injection into the joint under radiographic guidance. On the other hand, if your patient has ongoing leg or extremity pain after spine surgery, then the most common cause is unresolved or new nerve compression secondary to foraminal or lateral recess spinal stenosis. The first stage in diagnosing this problem is obtaining the appropriate imaging. Chronic ongoing foraminal stenosis, lateral recess stenosis and recurrent disc herniations are usually evident on an MRI or a CT myelogram. If nerve compression is suspected at a specific motion segment, then a well-directed transforaminal epidural steroid injection can diagnose and treat the patient’s pain. A recurrent disc herniation occurs in up to 10 percent of patients after a microdiscectomy and should always be suspected with a new onset of severe leg or arm pain. The final cause of ongoing leg or arm pain after surgery is true neuropathic pain. Usually no obvious nerve compression is evident on imaging. The patient describes a burning ache with occasional numbesss, and the pain is difficult to resolve with narcotics. Neuropathic pain rarely resolves with injections. In these cases, a spinal cord stimulator trial can be performed, and if the pain relief is excellent then the trial can be followed by percutaneous or open implantation of the stimulator. Recent studies have shown that over half of patients experience significant and long-lasting pain relief after receiving a spinal cord stimulator. With an appropriate workup, the cause of FBSS often can be successfully diagnosed and treated. We pride ourselves on our methodological approach to the treatment of FBSS, and would be glad to help your patients overcome this problem. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright © 2024 Providence Health & Services. All rights reserved. Clinical Trials | Quality and Outcomes | News and Events | About Us | Contact Us |

|||||||||||||||||