| Home News and Events |

|

eNeuroCould new therapies slow or even stop Alzheimer’s disease?

Michael S. Mega, M.D., Ph.D.

Medical director, Providence Cognitive Assessment Clinic Perhaps you have a patient who is worried about her memory or her problem-solving abilities. Or another who has complained about losing his car in the parking lot more than twice in the past month. Now that baby boomers are entering retirement age, our society is beginning to experience an epidemic in diseases related to aging. (One of my 82-year-old patients recently told me that he wanted to do everything he could to “die healthy”!)

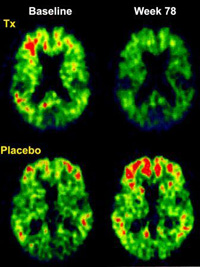

Figure 1: Brain amyloid burden, as measured through PIB-PET, has shown a 25 percent reduction in patients treated for 78 weeks with a monoclonal antibody against Aβ (top row). Patients on placebo are shown to have an increase in their Aβ burden (bottom row). Source: Lancet, 2010 So how can we avoid the decline associated with age-related brain diseases? This year we have seen the field of cognitive neuroscience make some significant advances. Over the past 25 years the hypothesis that a small 42-amino acid protein called amyloid-β protein may cause Alzheimer’s disease has instigated the pharmaceutical industry to bring anti-amyloid treatments into human trials. Within the past five years, two large, multi-center, placebo-controlled, anti-amyloid trials in mild to moderate AD patients have proved unsuccessful in slowing the progression of the disease. Perhaps this is because, as we now know, amyloid deposition peaks in the brain long before those affected lose the ability to function independently – the hallmark of being medically or legally demented. The best candidates for trialsThe pre-dementia stage of AD is called “mild cognitive impairment,” or MCI, and can last seven to 10 years. Amyloid deposition peaks during this stage, and we now know that cerebral spinal fluid levels of this protein, along with another called phosphorylated tau, impart a near 95 percent risk of developing AD within three years. People with very early AD or MCI may be the most appropriate to enroll in the anti-amyloid trials. Diagnosing and treating MCI and early AD is a focus of Providence Cognitive Assessment Clinic, given our participation in the international anti-amyloid clinical trials. Pre-referral screeningHow many animals can your patient name in one minute? Two experimental treatment protocols are actively being enrolled. One is an antibody against amyloid-β protein called bapineuzumab, which has recently been shown to reduce the brain amyloid burden by 25 percent, as shown in Figure 1. Another is an agent that decreases the production of amyloid-β protein by inhibiting a cleaving enzyme called gamma-secretase, freeing it from the mother molecule. This gamma-secretase inhibitor is the first anti-amyloid agent to be tested in a worldwide MCI trial. If these new agents merely delay decline from MCI to AD by five years, then the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in our society will be cut in half. A subset of patients may have a more robust response in that their disease could halt. With similar cognitive training as seen in post-stroke patients, they could return to normal functional levels. This flow chart may help with identifying early MCI patients. This is the hope for the next five years, and Providence Brain Institute will continue to offer these and other cutting-edge treatments for the Pacific Northwest. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright © 2024 Providence Health & Services. All rights reserved. Clinical Trials | Quality and Outcomes | News and Events | About Us | Contact Us |

|||||||||||||||||